On February 28, 2003, the local office of the World Health Organization in Hanoi, Vietnam, received a call from a small private hospital with a capacity of no more than 60 beds. Two days before, its staff admitted a patient showing symptoms of atypical flu. To rule out a potential case of “bird flu” they requested the help of WHO’s experts to try and determine what the disease really was.

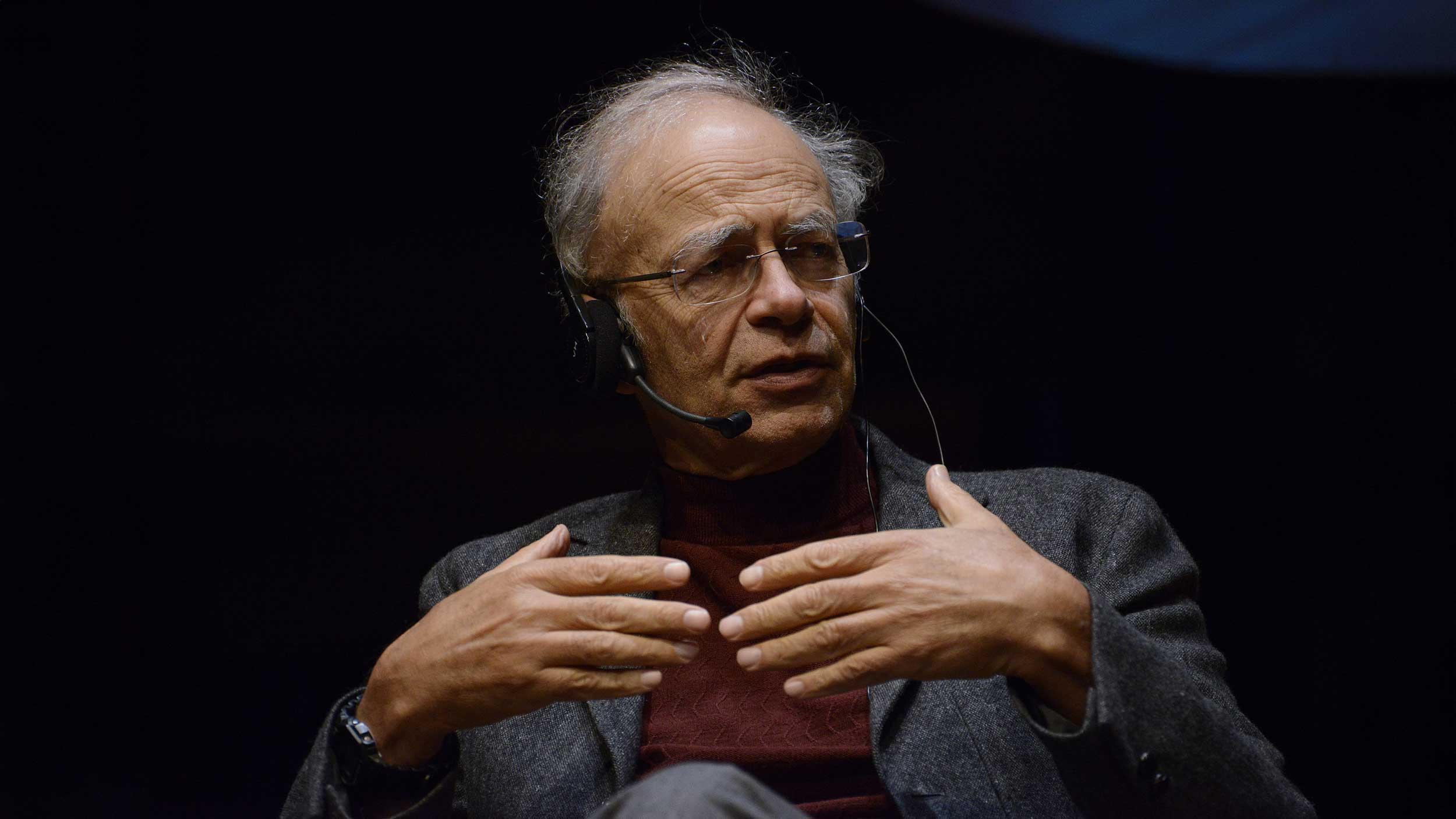

Their call was answered by Carlo Urbani, an Italian-born contagious disease specialist and Doctors Without Borders veteran who, as the president of the Italian section of this important medical society, was a member of the delegation which received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1999.

We do not know what kind of disease it is, but it is not flu

When Urbani, as the official representative of WHO, examined the patient named Johnny Chen, an American-Chinese businessman, it quickly became clear that the situation was very serious. He suspected the unfortunate businessman to have contracted a completely unknown disease that doctors had never heard of before and were therefore unable to tell how dangerous and contagious it was. Urbani and the hospital’s medical staff spent the following days collecting different samples and any other pieces of information they could gather from the patient, reviewed them and then sent them on to WHO, requesting immediate advice.

Urbani also made sure that a special secured, quarantined department was set up within the hospital. This soon turned out to be an important decision as one of the first conclusions the doctors were able to draw was that they were dealing with an extremely contagious disease. It was later found out that of the illness’ first 60 victims half were members of the medical staff. When doctors first presented symptoms of the disease they faced the difficult obligation of isolating themselves as well to avoid infecting their families and so spreading the disease across the city. So they stayed in the hospital for the entire duration of the research. In one of his reports to a colleague, Urbani said: “I am in a hospital full of crying nurses. People are running around, yelling, and are completely frightened. We do not know what kind of disease it is, but it is not flu.”

None of the precautions taken by the hospital’s medical staff turned out to be excessive. It soon became obvious that this was a case of a new viral disease which was not only highly contagious, but also very dangerous. They were unaware of this during the first weeks, but statistics later showed that one patient out of ten died. On March 9 WHO had already gathered enough information to meet with the highest representatives of the Vietnamese authorities and warn them about the gravity of the situation. Professional help from the international community had by this time begun reaching the hospital. Experts from abroad brought with them all the equipment developed and used in research of the most deadly and contagious diseases such as the Ebola virus. The private hospital was shut down and its patients were transferred to a special department of the Bach Mai public hospital where local doctors teamed up with members of Doctors Without Borders who were already used to dealing with similar situations.

When all the key precautions for fighting epidemics had been taken, the death rate stabilized. The outbreak of the disease in Vietnam became a good example of how to act when such a disease is suspected to have occurred. If Urbani had not been as convincing in warning the authorities to react as quickly and transparently as they did, we could have witnessed a catastrophe of epic proportions.

On March 11, soon after the situation in Hanoi was at least partially under control, Urbani flew to Bangkok to take part in a science conference. While still on the plane, he felt ill and already started showing typical symptoms of the newly discovered disease. A colleague was waiting for him at the airport, but he did not let him come near as it was obvious that the virus had attacked him as well. For over an hour, Urbani and his colleague sat quietly each on his side of the waiting room, waiting for the ambulance to bring all the equipment necessary for doctors to protect themselves from dangerous infections.

Urbani was taken straight from the airport to quarantine in a local hospital, where he spent the next 18 days fighting for his life. He developed the respiratory symptoms typical of all the virus’s other victims. He could only talk to his wife and three children over the phone because the infection was so dangerous that no one without adequate protection was allowed to come in direct contact with him. Despite his extensive knowledge of infectious diseases and the help of medical colleagues who flew in from Germany and Australia, bringing with them several new antiviral drugs, he finally lost his battle with the new and deadly disease. He died on March 28, 2003, a month after his expert advice was requested by the hospital in Hanoi. He left his diseased lung tissue to science.

The great Hong Kong virus carrier

Johnny Chen however, the businessman who brought the disease to Vietnam, was not the first to have been affected by the virus. WHO soon received information from other parts of the world about this new, highly infectious form of flu that quickly became known as SARS. In no more than a few weeks the disease had spread to three continents and it seemed that humankind was threatened by a pandemic of unforeseeable proportions. That is why on March 15 the WHO Director-General issued an alarming warning in which he urged that strictest precautions be taken in order to stop the pandemic.

Researchers later found out that the first case of SARS probably occurred in November 2002 in a Chinese boy from Foshan. On the November 16, 2002 he was admitted into the local public hospital with an atypical respiratory disease. How he had contracted the disease remains unknown, but we do know that he recovered after infecting several others who quickly spread the disease first across China and Hong Kong, then across the globe.

In China, the first “great disease carrier”, as epidemiologists call individuals who, due to their lifestyle or workplace, are likely to infect a large number of people, was a fish merchant called Zhau Zuofeng who caught the virus in January 2003 in Guangzhou. He not only transmitted the disease to the staff of three hospitals (at the end of the epidemic it was found out that 20% of all the infected were medical staff), but also to a nephrology professor who had just left for Hong Kong. There he stayed in room 911 on the ninth floor of the Metropole Hotel. After only ten days, the elderly professor succumbed to the disease after infecting several other guests of the hotel who were also staying on the ninth floor. In turn, they carried the disease to Toronto, Singapore and Vietnam. It was during his business trip from Shanghai to Hanoi that Johnny Chen, the man who carried the disease to Vietnam, made a stop in Hong Kong and spent the night on the ninth floor of the Metropole Hotel.

On March 15 when WHO issued a warning urging all travelers to be extremely cautious, no one knew much about the disease, except that it was a highly contagious form of atypical pneumonia. At first, experts suspected it was a modified flu virus, the symptoms of the disease indeed implied, but tests did not confirm this hypothesis. Because the lungs of the deceased were extremely damaged, suspicions arose that it might even be a case of lung plague, but as antibiotic treatment had no effect, this hypothesis was rejected as well. Soon, scientists agreed that SARS was the first serious new illness discovered in the 21st century.

A record-breaking discovery of the cause

On March 17 WHO assembled a team of the best microbiologists, virologists, epidemiologists, and clinicians in the world to battle against the new disease. With conferences being held daily and all the information transmitted via the Internet, it was established at the beginning of April that the disease was caused by a new virus of the coronavirus family which had never before been noticed in humans or in animals. Coronaviruses are relatively harmless and cause common colds. SARS, it seemed, was no typical coronavirus. By April 12, the scientists were already familiar with the entire genome of the virus and on the May 1 an article was published giving a detailed description of the virus.

In the middle of May, when the epidemic reached its peak and each day was filled with reports of several hundred new cases, scientists were still without any medication or vaccine to fight it, so the authorities had to resort to usual measures that have been practiced by humankind for thousands of years. All those contaminated were immediately isolated to prevent the disease from spreading further. In Singapore, webcams were installed in the homes of potential carriers of the virus, to ensure they kept the terms of their quarantine. The penalties for leaving quarantined homes were very severe. In Hong Kong, the apartment building in which the highest number of infected people lived was evacuated and its residents were moved to a special camp for ten days.

In China, it took longer for the authorities to realize the gravity of the situation. In the end, this was the reason why a quarter of all reported cases of SARS were from Beijing. Of course, it could have been even worse if, at a certain point in time, the Chinese authorities had not reacted so firmly. They shut down all the schools, theatres and cinemas, and prohibited all public events. At the end of April they decided to build a new hospital in the suburbs of Beijing which would specialize in treating SARS. Seven thousand construction workers set a record by constructing the hospital in no more than eight days for 170 million dollars. Then, as suddenly and mysteriously as the disease appeared, it began to vanish in the summer of 2003. Considering the fact that 774 people died of SARS, it was fortunate that only 8,096 people were infected.