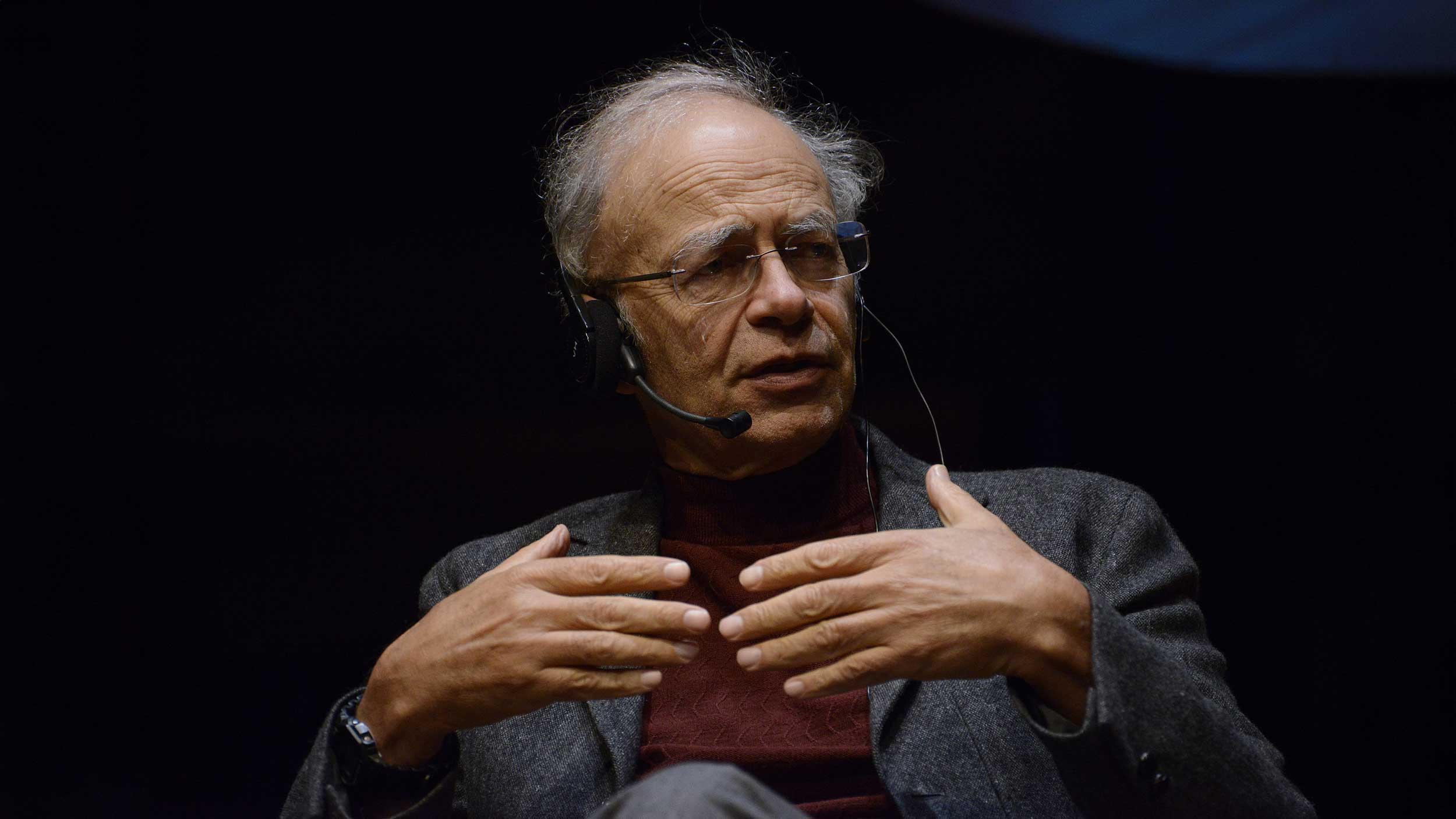

Peter Singer is a distinguished philosopher and professor at Princeton University, renowned for his work in bioethics and his role as a leading figure in the animal rights movement. Singer’s groundbreaking book Animal Liberation, published in 1975, catalyzed a global conversation on the ethical treatment of animals and continues to influence both public opinion and policy today. His advocacy for effective altruism has also inspired countless individuals to consider more impactful ways to improve the lives of others.

This interview was part of the science radio programme Frekvenca X on Slovenian Public Radio. The episode, entitled Effective Altruism Between Rationality and Emotions, was prepared by Luka Hvalc and Sašo Dolenc.

What are the most important strategies in the effective altruism movement at the moment, and where do you see the greatest potential for progress in the future?

Well, I think the most important strategies are essentially to spread the message that altruism is very good, but it’s even better if it’s combined with some research into what is most effective, and how you get the best value altruistically for the resources that you’re using. And in order to get a wide audience to listen to this message, I think it’s important to focus on issues that most people will immediately experience some concern about. Issues like helping people in extreme poverty in some of the least well-off countries of the world, or trying to reduce the suffering of very large numbers of animals confined in factory farms. There are certainly other issues that effective altruists talk about, but I think for gaining the largest audience, those two issues that I’ve mentioned are probably the most important.

Can you give some examples where the application of the principles of effective altruism has led to noticeable improvements in society? Which projects or organisations would you highlight as successful examples?

Well, the examples that are most successful are those that have used evidence in order to work out what the best thing to do is. So, for example, the Against Malaria Foundation is a very good example of that. It provides bed nets to protect people, especially children, against malaria in areas where malaria is a major killer of children, and, of course, makes adults very sick as well. And because there is research in this area that shows quite clearly that at a low cost, you can provide bed nets to people and that this will save lives, as compared with similar regions in which no bed nets are available. That’s a highly cost-effective thing to do with the resources that one has.

I also think that in the field of animal welfare, there’s good evidence that organizations trying to reduce the number of animals suffering in factory farms have had quite a lot of success and have helped very large numbers of animals. And that’s more effective in ending animal suffering than focusing on animals who, in some ways, are more emotionally appealing, like stray dogs, for instance.

How does effective altruism relate to other global challenges such as climate change, global inequality and others?

Effective altruism is a method that can be applied to any of these areas, including inequality and climate change. Certainly, climate change in particular is an area that effective altruists have been looking at, and they’ve been asking, where can we really make a difference here How can we have the most impact? And some effective altruists are recommending particular organizations that they think are more likely to have an impact in reducing, or mitigating the effects of climate change as compared with others.

When you mention global inequality, I think effective altruists are more likely to focus on the needs of people at the bottom rather than on equality or inequality in itself, because you can have a lot of inequality, even if there is nobody in extreme poverty. If there are some people who are getting by, getting enough to meet their needs, but still relatively poor, and then you have a few ultra-wealthy billionaires or people with even hundreds of billions of dollars, that’s a very unequal world. But effective altruists would tend to say, what’s really important is to help those who are worst off.

And if there are some people who remain extremely wealthy, that’s not in itself a problem. That’s only a problem if there are ways of redistributing the wealth to help people at the bottom, and maybe there aren’t such ways because, after all, if one country taxes billionaires very heavily, they’re mobile, they’ll just move to another country.

So, effective altruists would say, let’s do what can really make a difference by providing for the needs of those at the bottom rather than trying to find ways which are not very likely to be successful in redistributing the wealth of those who are billionaires. Well, individuals can certainly contribute in many ways. They can learn more about effective altruism, and there’s a lot of information online. They can form effective altruism groups in their own country. There are many effective altruism organizations in a variety of different countries.

I don’t really know if there is one in Slovenia. I hope there is, but if not, there’s an opportunity there to create one. And, apart from that, effective altruists can themselves think about what their particular concerns are: is it global poverty, is it animal welfare, is it the more far distant future and reducing the risk of our species becoming extinct? Then they can contribute to those concerns either by donating to them if they have some spare financial resources, or by volunteering for them and trying to spread the messages, trying to make more people aware of the effective altruism movement and of these particular causes.

How have your beliefs evolved over the years?

Well, I would never have called myself an effective altruist in the 70s because that term had not been coined. It was only coined maybe 15 years ago, maybe 15, maybe 18 years ago, but anyway, definitely in this century. I was an altruist, and I wrote about what we ought to be doing to help people who are starving or who are dying because of the lack of basic health care. I started writing about that in the 1970s, as you say, but I didn’t put enough emphasis on the idea of effectiveness, and I think that was a mistake.

That’s something that I’ve learned from the effective altruism movement and from the people who began that, people like Toby Ord and Will McCaskill in particular, and also those who have done the research on finding out what’s effective, and there I would think of organizations like GiveWell and the organization that I founded, The Life You Can Save, which particularly focuses on trying to curate a list of the most effective organizations helping people in extreme poverty.

How do you respond to the criticism that effective altruism may over-emphasise measurability and quantification, and may thus neglect important but less measurable aspects of human well-being?

I think that’s a legitimate concern. It’s true that effective altruists do want to emphasize measurable good because they feel that if that isn’t possible, you just can’t be sure whether you are doing good or how much good you’re doing. But it’s true that that may leave out some important causes. For example, advocacy for the poor is very difficult to measure because only occasionally will it have an important positive result, and when it does, then you need to balance that against the other occasions when it hasn’t, and it’s difficult to take all that into account.

Also, things like education, which are very long term in their benefits, are difficult to measure. It requires a long-term study, maybe 10 or 15 years, to see how extra years of education benefit people. Yet those things are important, and that is why The Life You Can Save has started to recommend organizations that work in the field of education, for example, just because of that concern. Whereas some of the other organizations that are more focused on what is measurable than The Life You Can Save do not recommend any organizations working in the field of education.

The movement was backed by several rich people, one of whom, a crypto-millionaire, has since gone bankrupt. How does this affect the movement?

There’s too much focus on a couple of individuals who are not really representative of the movement, but because they’re extremely wealthy individuals, everything that they say or do or everything that happens to them gets an enormous amount of press attention. I would say that in any large human enterprise there are going to be some things that go wrong : that’s just the way humans are.

Some people will do the wrong thing, and the media will report that, and people will think it’s representative of the whole movement. So, you know, I think that yes, Bankman-Freed was prominent. He talked about being an effective altruist, and I think that was genuine. I don’t think he was lying about that.

I think at the time that was his goal, and I think that what went wrong with FTX was more his incompetence and the incompetence of his team in running a business that had suddenly in a very short time grown to be a multi-billion dollar business, and they just didn’t have the financial structures in place to run it properly or even to know what their assets were. That’s one of the things that emerges from Michael Lewis’s book, Going Infinite, which is about Sam Bankman-Freed and the collapse of FTX.

The movement is much larger than these individuals, and I don’t think it should tarnish the reputation of the movement or of the many tens of thousands of people involved in it that a couple of people have done something wrong or said things that the rest of the movement probably doesn’t agree with.

How do you put effective altruism into practice?

I practice it by talking to people like you and trying to spread the message of the importance of effectiveness and the fact that by choosing, for example, to give to a charity that has been shown to be highly effective, you may do 10 times or even a hundred times or several hundred times as much good as if you gave to another charity, which is a perfectly genuine charity.

I’m not talking about frauds, but a charity that simply does not get as much good per dollar given. So, I think that’s a really important message to get across. Apart from that, I donate myself. I’m fortunate enough to have a more than adequate income, and so I donate substantially to the organizations that I think are most effective and that are doing the most to help people, and that particularly includes the Life You Can Save, which, as I say, is an organization I founded to help people in extreme poverty.

Thank you. It’s been a pleasure to speak to you and to reach a Slovenian audience.

Photo: Wikimedia.