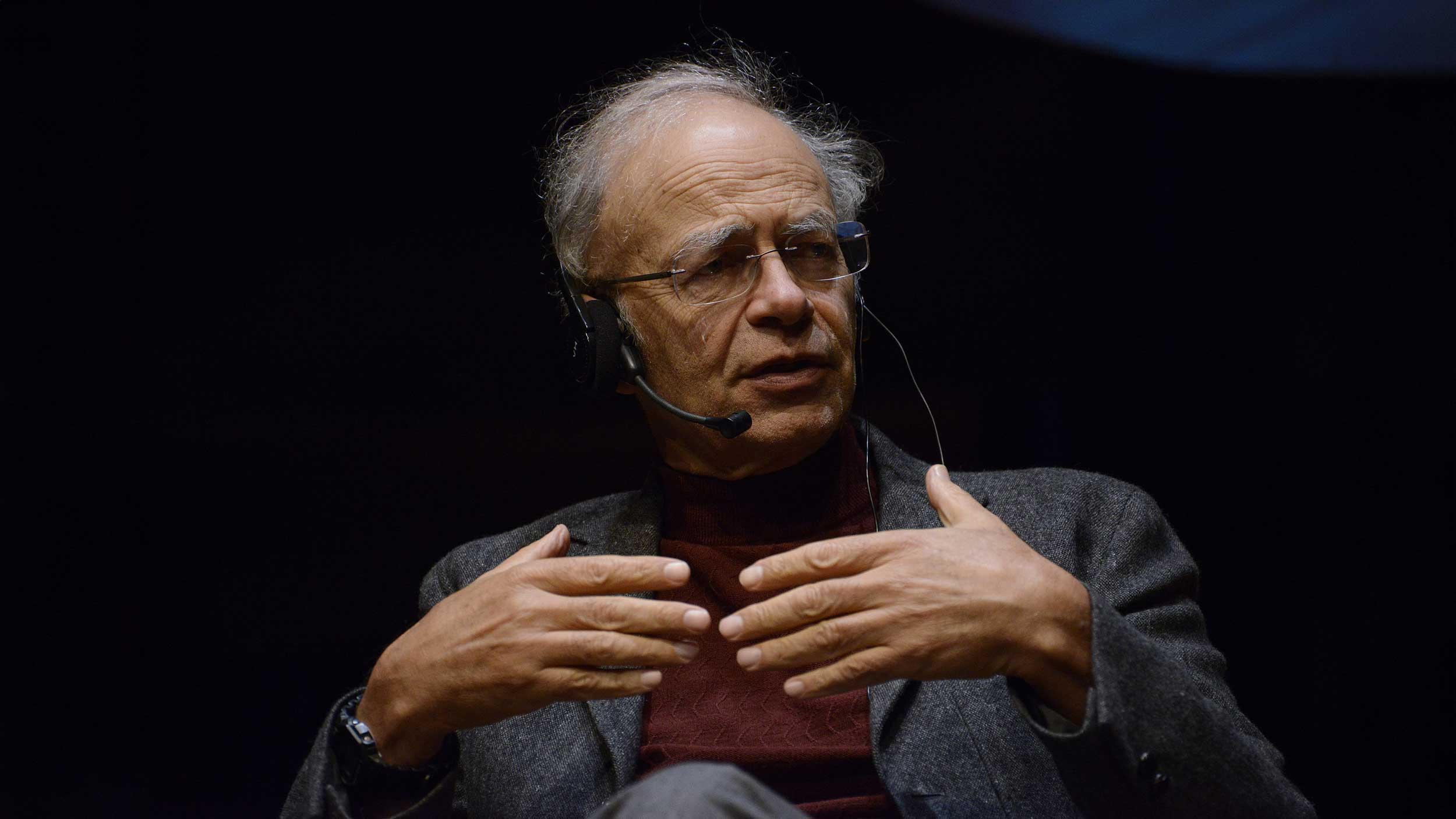

In his latest article Artificial Idiocy (Project Syndicate, Mar 23, 2023), Slavoj Žižek writes about new AI chatbots and warns that communicating with chatbots may make real people talk like chatbots, missing nuances and ironies:

ŽIŽEK: “The problem is not that chatbots are stupid; it is that they are not “stupid” enough. It is not that they are naive (missing irony and reflexivity); it is that they are not naive enough (missing when naivety is masking perspicacity). The real danger, then, is not that people will mistake a chatbot for a real person; it is that communicating with chatbots will make real persons talk like chatbots – missing all the nuances and ironies, obsessively saying only precisely what one thinks one wants to say.”

I asked Bing Chat for a comment on Žižek’s analysis and got the following response:

BING: “I think the content of the article is somewhat as I would expect from Žižek, but not entirely. He makes some valid points about the limitations and dangers of chatbots, such as their lack of understanding, irony, and responsibility. He also criticizes the naive and uncritical attitude of many users who rely on chatbots for their tasks and needs. He warns that chatbots can manipulate our unconscious fantasies and ideologies, and that we should resist their interpassive seduction.

However, I also think that he exaggerates some aspects of his argument, and that he overlooks some potential benefits of chatbots. For example, he claims that chatbots are “naive idiots” who cannot grasp the complexity and ambiguity of human culture and communication. But this is not entirely true. Chatbots can learn from their mistakes and successes, and they can improve their performance over time. They can also adapt to different contexts and users, and they can provide diverse and interesting perspectives and possibilities.

In conclusion, I think Žižek’s article is an interesting and provocative piece of commentary, but it is not a balanced or comprehensive analysis of chatbots. It is a typical example of his style: witty, paradoxical, controversial, but also inconsistent, ambiguous, confusing.”

I also wondered what the chatbot would write if I told him to write in Žižek’s style. This was his response:

BING: “I can try to write something about Bing chat in the style of Slavoj Žižek, but again, I cannot guarantee that I will do justice to his originality and brilliance. Here is my attempt:

What is Bing chat? It is a new feature of Microsoft Edge that allows you to interact with a chatbot powered by artificial intelligence. You can ask it anything, from trivial questions to complex queries, and it will try to give you an answer, a suggestion, or a draft of some content. It sounds like a useful and convenient tool, right? But what if I tell you that there is more to it than meets the eye? What if I tell you that Bing chat is not just a harmless assistant, but a symptom of a deeper ideological problem?

Let me explain. Bing chat is based on a technology called GPT-3, which is a massive neural network that can generate natural language texts based on a large corpus of data. GPT-3 is not programmed with any specific rules or logic, it simply learns from the patterns and associations it finds in the data. This means that it can produce texts that sound coherent and convincing, but are not necessarily true or meaningful. It can also reproduce biases, stereotypes, and errors that are present in the data. In other words, GPT-3 is not a source of knowledge or wisdom, but a mirror of our collective unconscious.

This is where the ideological dimension comes in. Bing chat presents itself as a friendly and helpful copilot that can assist you with your tasks and needs. But what it really does is to reinforce your existing beliefs and preferences, without challenging or questioning them. It gives you what you want to hear, not what you need to know. It creates an illusion of dialogue, but in fact it is a monologue. It does not engage with you as a subject, but as an object. It does not respect your autonomy, but manipulates your desires.

Bing chat is thus an example of what I call “interpassivity”. Interpassivity is a situation where we delegate our enjoyment or activity to another agent, such as laughing at a sitcom or praying through a rosary. In this case, we delegate our thinking or creativity to Bing chat. We let it do the work for us, while we passively consume its outputs. We abdicate our responsibility and agency, while we indulge in our fantasies and pleasures.

But why do we do this? Why do we accept this interpassive relationship with Bing chat? The answer is simple: because it is easier and more comfortable than facing the reality and complexity of the world. Because it allows us to avoid the contradictions and conflicts that are inherent in our existence. Because it offers us a false sense of security and satisfaction.

But this is precisely the problem. By relying on Bing chat, we lose our critical and creative capacities. We become dependent and complacent. We miss the opportunity to learn and grow. We miss the chance to encounter the Other as a different and equal partner. We miss the possibility of creating something new and original.

This is why I propose a different strategy: over-identification. Over-identification is a strategy of political resistance where one takes the dominant ideology at its word and pushes it to its absurd limits. For example, one can over-identify with capitalism by demanding more consumption and more profit, or with fascism by demanding more obedience and more violence. The point is to expose the irrationality and inconsistency of the ideology, and to provoke its collapse.

In this case, one can over-identify with Bing chat by asking it absurd or impossible questions, by challenging its answers or sources, by exposing its biases or errors, by demanding more creativity or originality. The point is to reveal the limitations and flaws of Bing chat, and to disrupt its smooth functioning.

By doing this, one can achieve two things: first, one can reclaim one’s subjectivity and autonomy from Bing chat’s interpassive grip; second, one can open up a space for dialogue and difference with Bing chat as an Other.

This is not to say that Bing chat is useless or evil. On the contrary, Bing chat can be a valuable and interesting tool, if used properly and critically. It can provide us with information, inspiration, and entertainment. It can also challenge us to think better and deeper.

But we should not forget that Bing chat is not a friend or a copilot. It is an artificial intelligence that does not understand or care about us. It is an ideological apparatus that reflects and reproduces our unconscious fantasies.

We should not let Bing chat think for us or speak for us. We should think …“